Did you know that hysteria as a medical diagnosis was only removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1980?! Things have come a long way in the treatment of women’s health, but we still have a way to go.

We spoke to Sarah Graham, a freelance journalist and owner of Hysterical Women, a feminist blog which explores sexism and disbelief around womens health care, to find out more about the history of hysteria and why womens health concerns aren’t always treated seriously.

Thanks so much for talking to us! Could you start by describing the word hysteria and what it has traditionally meant?

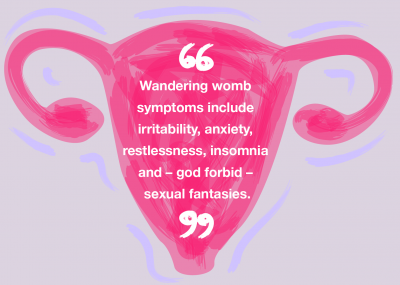

Hysteria as a concept has been around since the Ancient Greeks. Originally, hysteria was believed to be a physical condition to do with the womb. It was this idea of the wandering womb which caused women to have particular ailments.

The most well known definition of hysteria is Freudian hysteria. It’s based on the assumption that there’s something inherently faulty about women’s bodies, their brain chemistry, their hormones and their wombs which makes women prone to being unwell in various ways.

Today, it’s still associated with this idea of women being over the top and melodramatic. It’s this idea that women are overly emotional, that they’re not the most rational. There’s also this idea that it’s just your hormones because you’re a woman, particularly with period pain and Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS). They’re kind of normalised. It’s as if to be a woman is to be in pain and we should just put up with it.

When and why did you start Hysterical Women?

I started it in October 2018. I met up with a women’s health campaigner for a drink and we had a really fantastic ‘putting the world to rights’ conversation and I came away feeling really inspired.

I’d been working on stories around women’s health and I was seeing the same patterns coming up again and again. Themes of feeling dismissed, feeling they weren’t taken seriously and that they were being misdiagnosed or having to wait years to get a diagnosis.

Great things happen when women come together and talk about these things. I wanted more of a community and a space for multiple voices rather than just my own. I wanted to give a voice to women’s experiences beyond what I was doing with my journalism.

Do you think it's important to reclaim the term ‘hysterical’?

To some extent, that’s what I’m trying to do with my blog. It’s about highlighting the way women can be treated within medicine.

I think today in particular a lot of that is unconscious. Healthcare professionals are not setting out to discriminate against women because they hate women. It can be deeply ingrained. I think it’s a big systemic problem. I think that by highlighting it and calling it out, hopefully it makes people more aware of it.

For patients, I hope that it makes them think: ‘Okay, it’s not just me. There are loads of other women having these experiences.’

I’m always really struck when women who write for the blog say things like ‘I always thought it was just me. I thought I was going mad. The doctor was saying that it was all in my head. And I got to the point where I believed them because I just thought they must be right. I must be just losing the plot.’

I hope that by reclaiming it, it draws attention to the fact that although hysteria is no longer an official medical diagnosis, unconscious bias does still exist and women are still experiencing the effects of it.

Do you think it's exclusively men who are dismissive of women's complaints?

It’s definitely not exclusively male. There are some brilliant male doctors, there are some brilliant female doctors. It’s really important to highlight that the medical profession as a whole is fantastic. I’m not about slating doctors as individuals or as a group.

There are very few doctors who are consciously making a choice to be sexist or discriminatory, but you see unconscious bias across the board. One of the examples that I quite often use is with period pain.

Period pain is one of those really subjective experiences, because as a woman your only experience of period pain is your own. If you’re a female doctor, it’s very difficult to imagine what painful periods might be like for someone else. You often get the attitude of: ‘Oh it’s normal. We all get it. You just have a paracetamol and a hot water bottle and you’ll be fine.

Are there any examples of health conditions which affect women and are misunderstood or perhaps not given enough attention?

The number of women with diabetes is similar to the amount with endometriosis, but funding for diabetes research is staggeringly more than endometriosis patients could even dream of.

There have been some successful awareness campaigns around endometriosis recently. More is being done, but it’s not there yet considering how many people it affects and how little is still known about it.

Do you think there is a stigma attached to women's health particularly with periods and issues that sometimes arise around contraception

We have started getting better at having those conversations, but there is still a massive amount of stigma, shame and misunderstanding around women’s bodies.

It’s largely just because we have never really talked about it. It’s seen as something dirty and shameful. For teenage boys, for example, masturbation is seen as kind of a rite of passage, but it’s just not talked about with teenage girls.

Everything to do with female bodies and female sexuality is very hush-hush, you have the period talk which is only given to girls while boys are taken off separately to talk about wet dreams. It’s presented to us as something private, secret and shameful that you don’t talk about.

Contraception is often seen as something that is women’s problem and women’s responsibility, rather than something that couples should talk about collaboratively.

It’s just about having more of these conversations together, whether it’s about periods, whether it’s about contraception or just anatomy in general.

Do you think emergency contraception is especially stigmatised?

Yeah, totally. Things have improved, the fact you can get it over the counter is a great thing, but there is still that level of shame in having to justify yourself rather than just being able to walk into a shop and buy over the counter like you would with condoms.

I’m sure that most pharmacists are very sympathetic, understanding and don’t try to make women feel ashamed, but there’s this idea that women have been silly, irresponsible and reckless to have ended up in that situation, which is just nonsense. Things happen, things go wrong.

I don’t remember my school sex education mentioning emergency contraception. I was never taught that it’s an option if the condoms fail or you’re caught in the heat of the moment. It was thought of as something that was for women who’ve been reckless, stupid and hadn’t been taking sensible precautions. It had that association with promiscuity. Which now obviously I know is not the case. There could be a whole plethora of reasons why you might need it.

A lot of women don't know how emergency contraception works. Why do you think that is?

I think it is partly because of shame. This idea that the only people who need emergency contraception are people who have been irresponsible and reckless. It’s one of those things where you never think that’s gonna happen to you.

Everyone thinks ‘that’s that’s not for me that’s, you know, that’s different types of women’. No one wants to take emergency contraception. That’s why it’s called emergency contraception because you take it in emergencies. It’s not something you usually plan for. I think because of that it’s just not talked about and there is this shame and stigma attached to it.

The first time most women research emergency contraception is the first time they use it. If you’re in that state of panic, you probably aren’t doing in-depth research. I think it’s a combination of circumstance and that stigma.

How can we encourage more women to come forward and speak about their experiences of maybe not being taken seriously?

The more the more we have those conversations, the more women will naturally and organically come forward.

I think one of the things I’m always really struck by is people saying that they thought they were the only one who’d experienced this. They thought they were going mad. They thought it was all in their head, but actually reading these experiences is really validating.

—

The more we share, and the more these conversations open up, the more people feel able to join in that conversation.

Great things happen when people come together and the more we talk about things the more they lose their stigma and come out of the shadows. If you have taken the morning after pill, please consider sharing your story below to help us end the stigma which still surrounds this experience.

No healthcare providers mentioned in this piece endorse any products or brands.

By: Sophia Moss

ellaOne® 30mg film-coated tablet contains ulipristal acetate and is indicated for emergency contraception within 120 hours (5 days) of unprotected sex or contraceptive failure. Always read the label.